Golf Carts w/missing wheels: Rebutting Sen. Lankford's CNN Appearance, Part 2

Yesterday I corrected a bunch of factual misstatements (aka "lies") and gross exaggerations about the ACA's premium tax credits and the GOP's refusal to extend the enhanced subsidy formula made by Oklahoma Senator James Lankford in his appearance on CNN's State of the Union with host Kasie Hunt.

Today, I'm addressing the most critical exchange of his appearance:

LANKFORD: "I would tell you uh healthcare in 2010 before Obamacare kicked in. Healthcare in 2010 the normal premium was $215. $215. Now take what it is now after Obamacare has been put in place and I think the..."

HUNT: "...Right, but insurance companies could could refuse to cover you for a pre-existing condition. I mean the health care system was vastly different before Obamacare for for many of those reasons."

This is the crux of the matter: Saying that individual health insurance market policies cost less in 2010 than ACA plans do today is like complaining that a used golf cart with a missing wheel cost less in 2010 than a Honda CR-V does today. It's technically accurate but also completely irrelevant.

To explain why, I'm going to once again dust off the Psychedelic Donut® and the Three Legged Stool®.

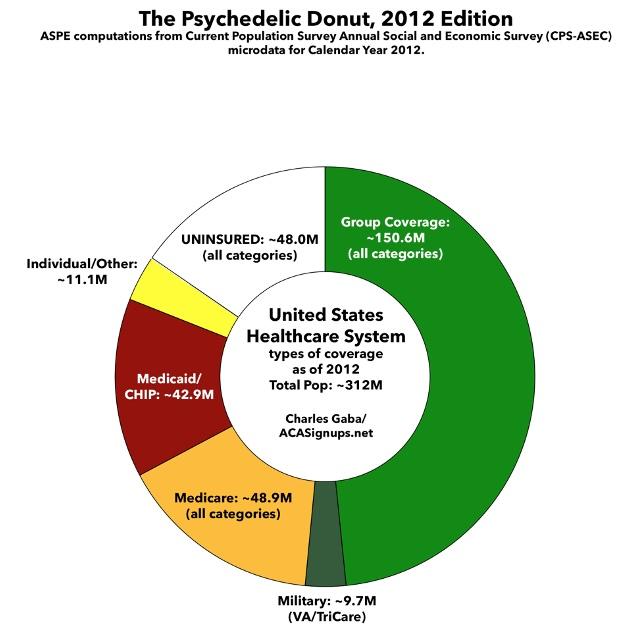

This donut graph represents the types of healthcare coverage the entire US population had as of 2012. This was shortly before most ACA provisions went into effect:

Around half the population was enrolled in some sort of employer-based coverage, including the U.S. military. Another ~30% were enrolled in either Medicare, Medicaid, or the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

Perhaps ~11 million were enrolled various types of "non-group" or "individual market" plans directly through insurance carriers...and around ~48 million Americans, over 15% of the total population, had no healthcare coverage at all.

The ACA had two main goals: First, to reduce the number of uninsured Americans as much as possible by making coverage less expensive and more accessible; and second, to provide consumer protections from industry abuses to everyone, but ESPECIALLY those in the individual market, where the abuses were the worst.

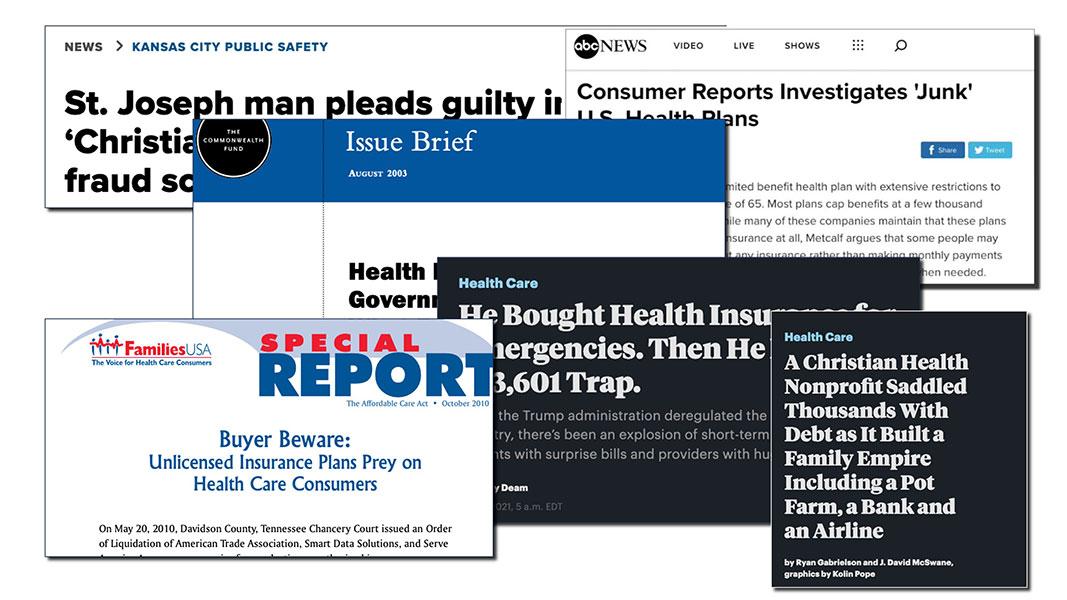

Before the ACA, the individual market was basically the Wild West. Much of the coverage was "junk plans,", covering very little. There were some exceptions, but it was mostly a crapshoot, with few standards and very little regulation in most states.

Pre-ACA nongroup plans were a hodge-podge, including an array of patchwork policies known as Mini-Meds, Short-Term Plans, Farm Bureau Plans, Association Plans, Sharing Ministries and so on...some of them not even legally defined as health insurance.

To give you an idea of how stingy some of these plans were, here's a few examples from before most ACA individual market regulations went into effect:

For example, McDonald’s”McCrew Care" benefits requires employees to pay $56 per month for basic coverage that provides up to $2,000 in benefits in a year and $97 per months for a Mid 5 plan that provides up to $5,000 in benefits. Ruby Tuesday charges workers $18.43 per week...for coverage that provides up to $1,250 in outpatient care per year and $3,000 in inpatient hospital care. Denny’s basic plan for hourly employees in 2010 provided no coverage for inpatient hospital care and capped coverage for doctor office visits at $300 per year.

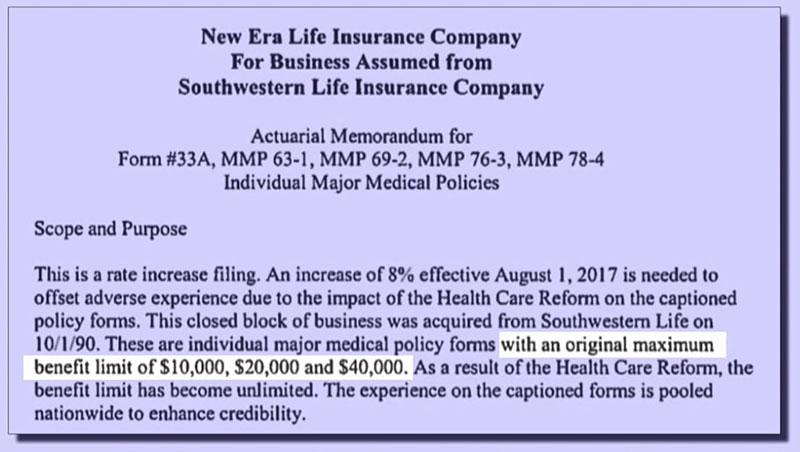

Even many so-called "major" medical plans often had extremely skimpy benefit limits, like this one which capped coverage at no more than $40,000 per year.

The maximum cap was more typically in the $1 - $2 million range, which sounds like a lot...but that was often your LIFETIME cap, and if you had to undergo chemotherapy, or gave birth to a preemie who had to stay in a neonatal unit for a few weeks, you'd find out how quickly that could add up. Not that it mattered since many of these policies didn't cover maternity or neonatal care anyway.

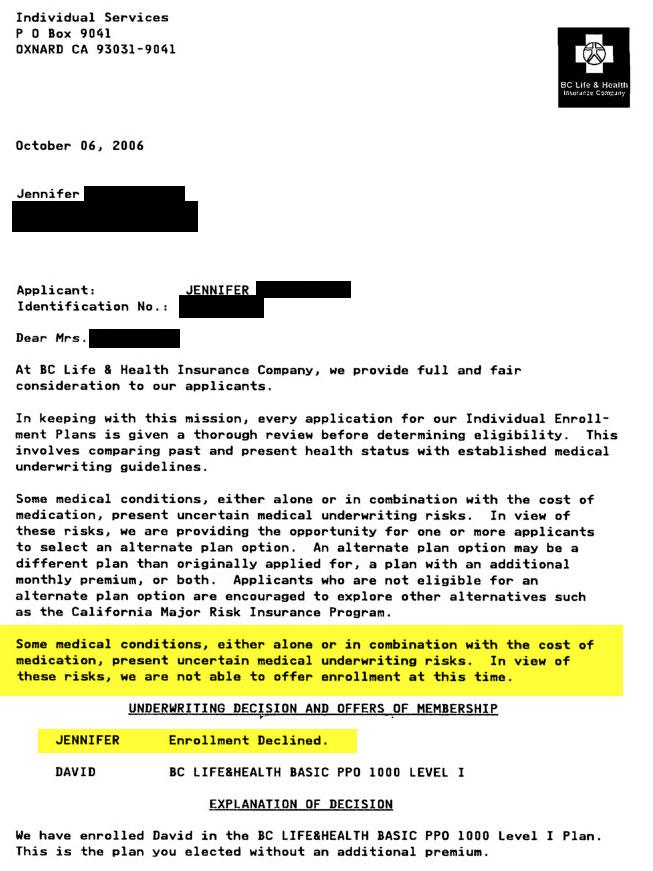

The biggest issue with individual market coverage prior to the ACA was that insurance carriers could cherry pick who they'd allow to become enrollees, what they'd be covered for, and how much of the claims they felt like paying for, if anything.

For example, just the other day someone on Bluesky posted a scan of an actual rejection letter she received from a health insurance company in 2006 (four years before the ACA passed and eight years before the ACA regulations were fully ramped up). She gave me permission to use it here:

That brings us to risk pools.

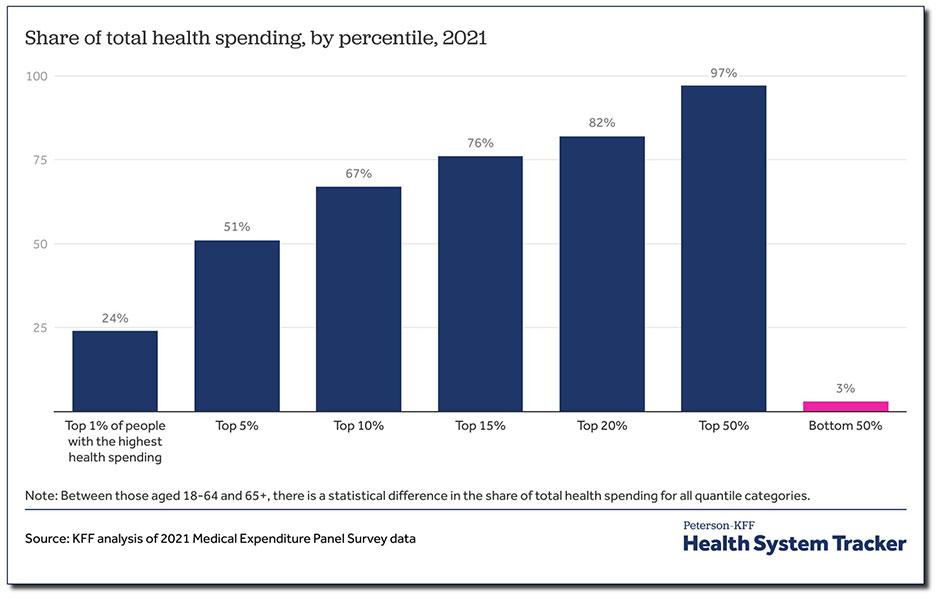

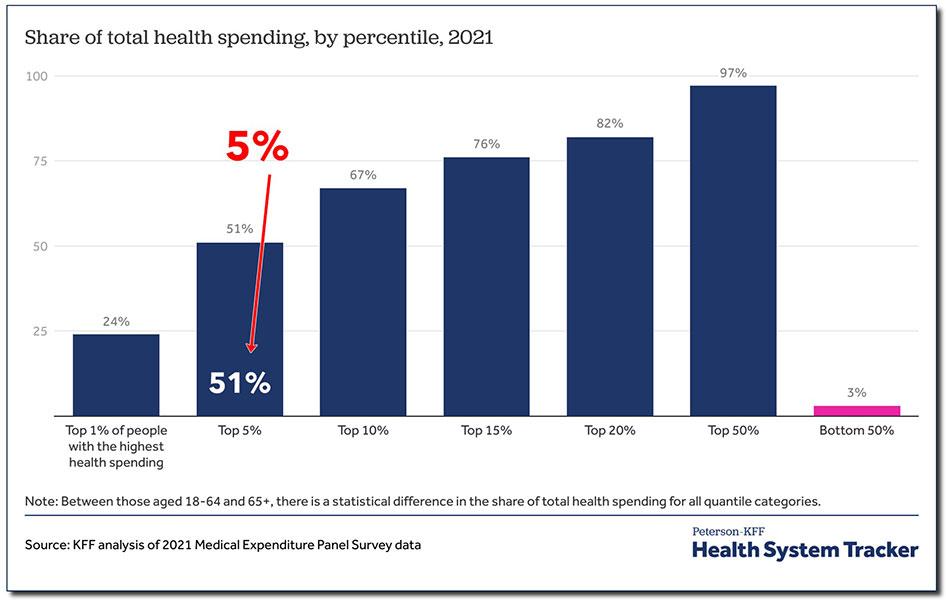

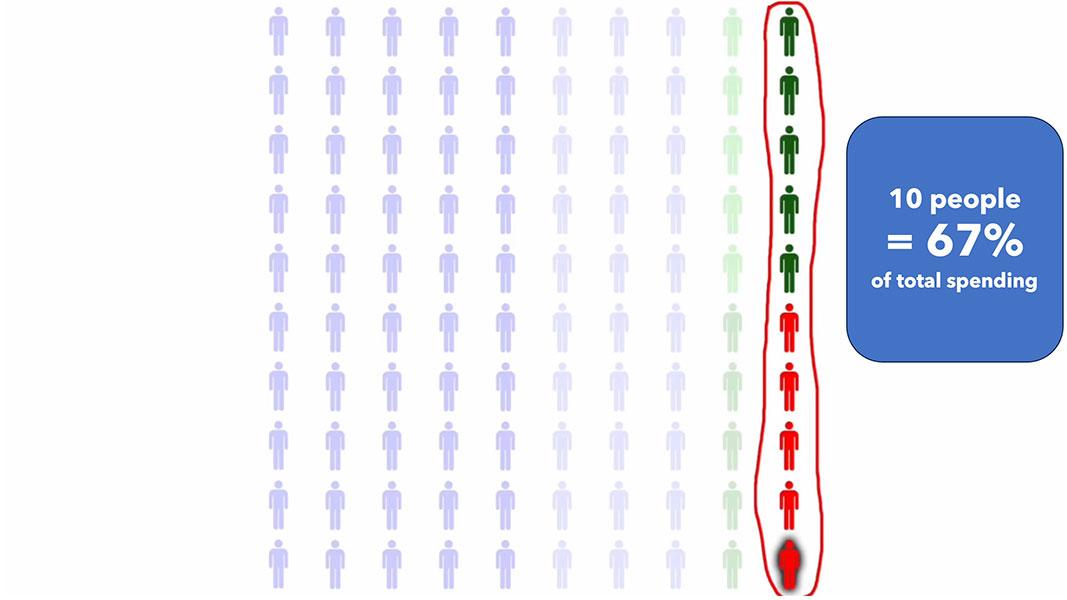

According to KFF, this is the breakout of total healthcare spending among the U.S. population. The proportions change slightly from year to year, but it's been remarkably consistent for decades.

Generally, the unhealthiest 1% of the total population accounts for around a quarter of total healthcare spending.

When I say TOTAL, I mean doctors, nurses, hospitals, clinics, prescription drugs, medical equipment...everything, regardless of who's paying the bill.

5% of the population accounts for over half of total healthcare spending; and 50% of the population accounts for full 97% of all healthcare spending.

Total healthcare spending in the United States reached $4.5 trillion in 2022. Again, when I say total I mean everything: Medicare, Medicaid, the ACA, the VA, the IHS; all private insurance, all premiums, deductibles & co-pays...everything. All of it came to $4.5 trillion, or an average of $13,500 apiece.

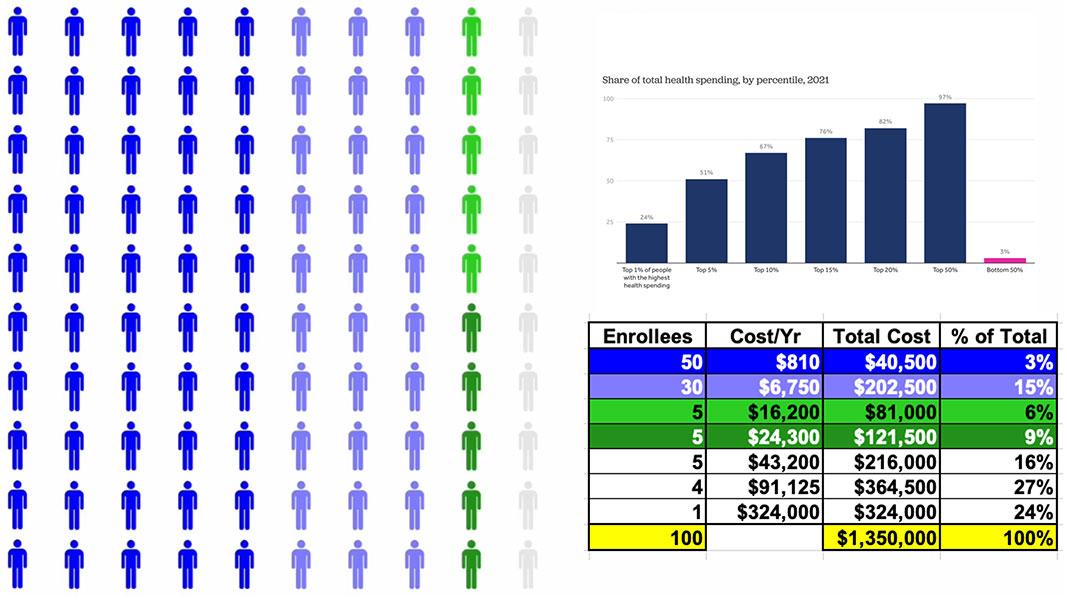

Let's suppose we boil the entire population down to exactly 100 people.

At $13,500 apiece, the total aggregate healthcare spending for all 100 would come to around $1.35 million.

Some of them won't require anything more than an annual physical. Some may come down with a nasty flu. Some may break their finger and require a splint or physical therapy. Some of them may require complex surgery like a coronary bypass.

And finally, a few will come down with serious, expensive medical issues like cancer or diabetes.

Using the KFF graph, this is how that $1.35 million breaks out across all 100 people. Half only need around $800/year in medical spending; another 30 would run $6,700 apiece, and so on.

90% of them would only add up to 1/3 of the total.

That leaves the remaining 10% racking up the other 2/3, including one poor soul who would require hundreds of thousands of dollars in healthcare spending per year.

So, let's suppose that all one hundred of these people want to buy health insurance directly from a carrier.

Before the ACA, the carrier would stop them and say: First you need to tell me, in explicit detail, your entire medical history.

That's every medical diagnosis; every hospital visit; every prescription; every lab test; every surgery; every x-ray; EVERYTHING.

Then, an actuary would pore over all of your records and decide whether to allow you to enroll...or kick you to the curb.

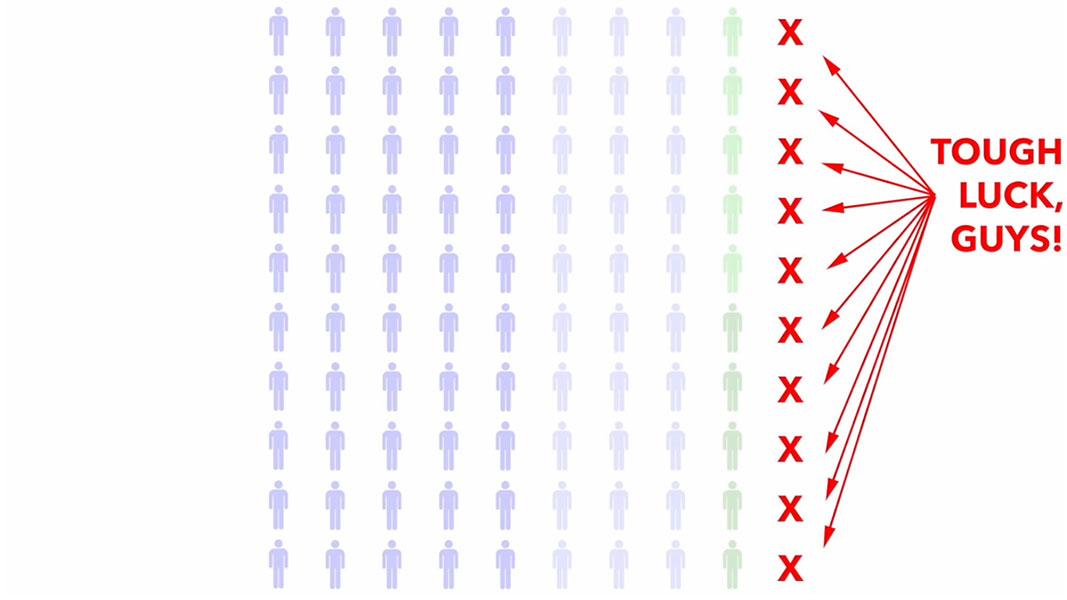

Basically, they were weeding out the 10% of the population which eats up 2/3 of total healthcare spending. This is called Medical Underwriting, and it was the single biggest reason why people were told "no dice," denied coverage & had to try elsewhere.

By cutting off the most expensive enrollees, they were left with 90 people at 1/3 the claims cost.

For those 90, the average healthcare costs just dropped from $13,500 each to under $5,000.

Side note: In 2010 (the year Lankford chose for his "$215/month" claim, even though the ACA didn't really ramp up until four years later), the actual per person average was more like $8,400 apiece, 1/3 of which would be $2,800/year or...$233/month, which is pretty damned close to Lankford's $215 figure. Imagine that!)

This is why, ON THE SURFACE, pre-ACA individual market premiums were relatively inexpensive...for those deemed healthy & low-risk enough to be allowed to enroll at all.

But what about the other ten?

They were often deemed "uninsurable at any cost" and effectively blacklisted by the insurance industry for having "Pre-Existing Conditions."

So, what counted as a "Pre-existing condition" which might mean you got kicked to the curb? Well, here's a list of the most common ones...

- AIDS/HIV

- Alcohol abuse/ Drug abuse with recent treatment

- Alzheimer’s/dementia

- Arthritis (rheumatoid), fibromyalgia, other inflammatory joint disease

- Cancer within some period of time (e.g. 10 years, often other than basal skin cancer)

- Cerebral palsy

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/emphysema

- Congestive heart failure

- Coronary artery/heart disease, bypass surgery

- Crohn’s disease/ ulcerative colitis

- Diabetes mellitus

- Epilepsy

- Hemophilia

- Hepatitis (Hep C)

- Kidney disease, renal failure

- Lupus

- Mental disorders (severe, e.g. bipolar, eating disorder)

- Multiple sclerosis

- Muscular dystrophy

- Obesity, severe

- Organ transplant

- Paralysis

- Paraplegia

- Parkinson’s disease

- Pending surgery or hospitalization

- Pneumocystic pneumonia

- Pregnancy or expectant parent

- Sleep apnea

- Stroke

- Transsexualism

...but guess what? You could also be be denied coverage for having had acne, "back problems," high cholesterol or clinical depression.

But that's not all! There was also an extensive list of occupations which could be denied coverage entirely--air traffic controllers, meat packers, pilots, scuba divers, taxi drivers (which I'm guessing would include Lyft or Uber drivers today).

Essentially, a "pre-existing condition" was really defined as "whatever the hell the insurance carrier felt like calling one."

In some cases carriers WOULD offer coverage...at several times the normal rate. In other cases they'd offer a policy which covered everything EXCEPT the one condition they were in most desperate need of the policy to cover in the first place.

Finally, many policies simply flat-out didn't cover services like maternity care, prescription drugs or mental health services at all.

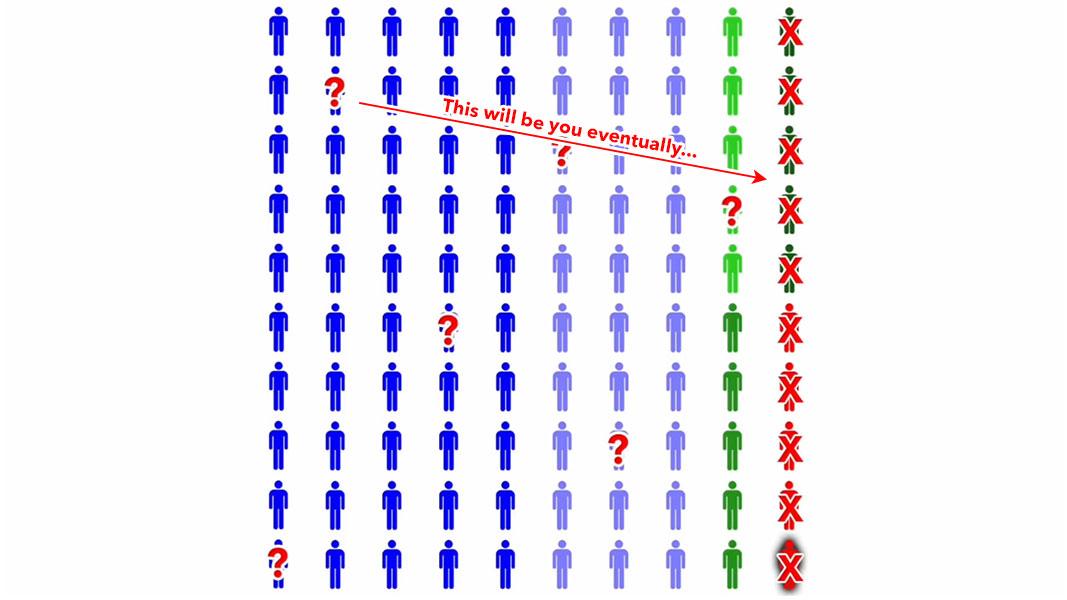

Now, if you're healthy and don't have a soul, you might not give a shit about sick people being thrown under the bus as long as it cuts your healthcare costs down...but there's still a big catch even for the amoral:

People who are healthy today get sick & injured too.

On a long enough timeline, pretty much EVERYONE develops one or more serious medical conditions, putting them into the other 10%.

Again, there WERE some options for folks who were denied comprehensive coverage by legitimate insurance carriers, but they ranged from so-so to practically useless, and in many cases were run by fly-by-night outfits participating in outright fraud.

Oh yeah...I almost forgot about one of the nastiest things that even legitimate insurance carriers used to do: rescission.

Every once in awhile some enrollees who the carrier had carefully cherry-picked to ensure that they were healthy would actually (gasp!) be diagnosed with some expensive ailment anyway.

At that point, some carriers would retroactively cancel their policy & refuse to pay claims over some minor/nominal paperwork error/omission:

Rescission (also known as "post-claims underwriting") is the process whereby health insurers avoid paying out benefits to treat cancer and other serious illnesses by seeking and often finding chickenshit errors in the policyholder's paperwork that can justify canceling the policy. In one job evaluation, the health insurer WellPoint actually scored a director of group underwriting on a scale of 1 to 5 based on the dollar amount she had managed to deny through rescission. (The director had saved the company nearly $10 million, earning a score of 3. WellPoint's president, Brian A. Sassi, insists this is not routine company practice.)

Rescission's victims tend typically to be less-educated people who are more likely to make an error in filling out their insurance forms and lack the means to challenge a rescission in court—a path in which success is, at any rate, not guaranteed, because under state law the practice is perfectly legal if done within the allowable time frame (typically up to two years after a policy is issued).

The health crisis doesn't get more gothic than this. Robin Beaton, a retired nurse in Texas, was rescinded last year by Blue Cross and Blue Shield after she was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer. Blue Cross said this was because she had neglected to state on her forms that she had been treated previously … for acne. Beaton eventually persuaded her congressman, Rep. Joe Barton, to twist Blue Cross' arm, but the delay meant it was five months before she could receive her operation.

Otto Raddatz, a restaurant owner in Illinois, was rescinded in 2004 by Fortis Insurance Co. after he was diagnosed with non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Fortis said this was because Raddatz had failed to disclose that a CT scan four years earlier had revealed that he had an aneurism and gall stones. Raddatz replied—and his doctor confirmed—that he had never been told about these conditions (the doctor said they were "very minor" and didn't require treatment), but Fortis nonetheless refused a payout until the state attorney general intervened.

Now that I've explained the problems in the individual market before the ACA, here's how the law attempted to fix them.

1. Guaranteed Issue

First, it required that all major medical policies be given guaranteed issue status. This means insurers have to offer them to anyone who wants to enroll, regardless of health condition, medical history or other factors. They can't even ASK about health or medical history.

2. Community Rating

Next, all major medical plans have to be Community Rated, which means premiums, deductibles, copays & coinsurance can't vary based on anything other than how age, where they live, and whether or not they smoke.

3. Essential Health Benefits

Next: The ACA requires all major medical plans to include coverage for ten essential health benefits, or EHBs, including: Outpatient services, emergency care, hospitalization, maternity & newborn care, mental health & substance abuse, prescription drugs, rehab services, lab services, preventative services, & pediatric services.

4. Minimum Actuarial Value

ACA-compliant plans also have to have a minimum Actuarial Value, or AV. This refers to what percent of average healthcare expenses the plan pays for, in aggregate. ACA plans generally have to have AVs between sixty to ninety percent, with metal level designations--Bronze, Silver, Gold or Platinum. Generally, Bronze plans, which have a 60% AV, have the lowest premiums but the highest deductibles, while Platinum plans, at 90% AV, have the highest premiums but minimal deductibles.

5. No more Annual/Lifetime Benefit Limits

In other words, a premature infant who spends the first weeks of their life in a neonatal unit at anywhere from $4,500 - $160,000 per day is no longer doomed to being uninsurable for the rest of their life before they've even left the hospital.

6. Maximum Out of Pocket Ceiling

Next: ACA plans eliminate both the annual & lifetime benefit caps. At the same time they have to INCLUDE a cap on out-of-pocket expenses for in-network care. This is called Maximum out-of-Pocket or MOOP, which includes the deductible, co-pays & coinsurance. Anything over the MOOP for in-network care has to be paid for by the carrier.

Admittedly, the MOOP is still pretty damned high ($10,600 for one person this year, $21,200 for a family...which are $450 & $900 higher than they otherwise would have been due to a regulatory change made by the Trump Regime earlier this year, I should note), but it at the very least prevents your family from going completely bankrupt in a worst-case catastrophic scenario.

7. No-Cost Preventative Services

ACA plans have to cover a long list of preventative services at no out-of-pocket cost to the enrollee, as long as they performed by an in-network provider.

This includes things like annual physicals, mammograms, blood screenings, immunizations, colonoscopies and so forth.

8. Stay on Parents Plan until 26

Under the ACA, Insurance carriers must allow Young Adults to stay on their parents plans up to age 26.

9. Rescission outlawed except in cases of clear & deliberate fraud.

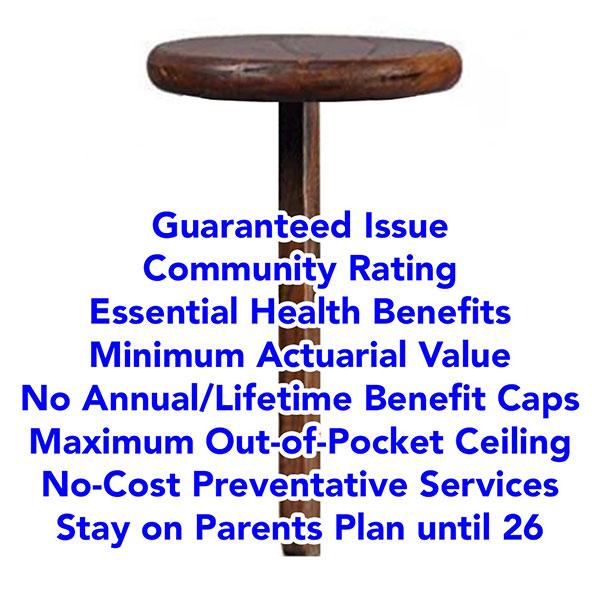

When you add all of these together, you create a 1-Legged Stool.

However, when you require policies to be comprehensive, but also DON'T have any restrictions on who can enroll or when they can do so, healthy people tend not to enroll at all until they get sick or injured.

This causes premiums to shoot up for those who do enroll, which in turn causes more low risk enrollees to drop out, which in turn causes premiums to increase even more, causing more people to drop out and so on.

It's like waiting until you crash your car to get auto insurance, or waiting until after your house catches on fire to buy homeowner's insurance.

It's the reason why you can't drive a car without auto insurance and you can't get a mortgage without homeowners insurance.

The flip side of this is that putting healthy people into the same risk pool as unhealthy people--which is kind of the entire point of health insurance in the first place--means that yes, some people would have to start paying more than they otherwise might have until their situation changes (ie, until they get sick or injured themselves...which, again, is the entire reason health insurance exists)...which is why the ACA also includes financial assistance to help make the dramatically more comprehensive coverage affordable for enrollees, on a sliding income scale.

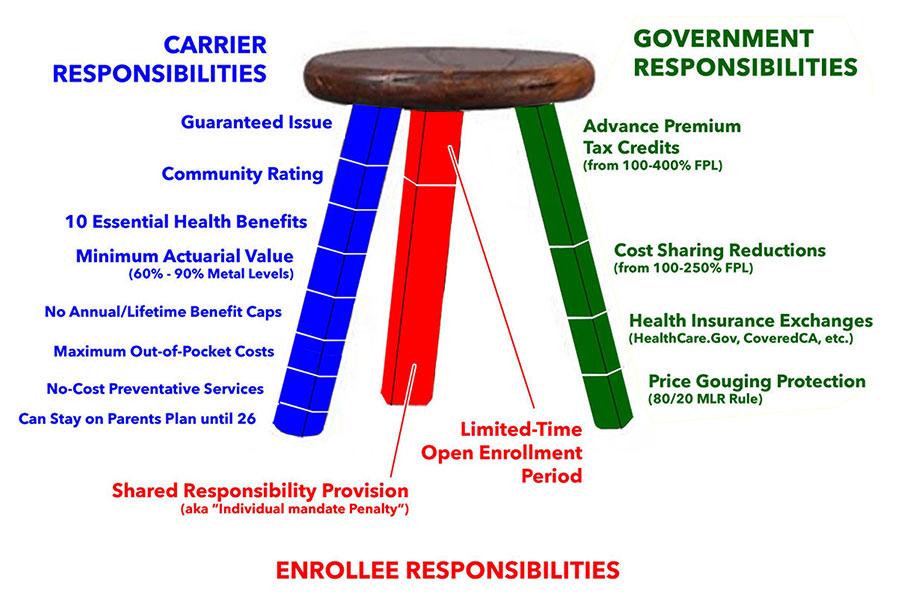

In short, the ACA uses a THREE-Legged Stool instead, based on the Massachusetts model:

The first leg, Carrier Responsibilities, includes everything I just talked about: Guaranteed Issue, Community Rating, Essential Health Benefits, Minimum AV, Elimination of Annual or Lifetime Caps, Maximum Out-of-Pocket costs, Zero-Cost Preventative Services, Young Adult on their Parents Plans until 26 & some other requirements.

The other two legs include carrots & sticks.

The red leg--the sticks--included the controversial Individual Mandate Penalty, along with a limited-time Open Enrollment Period, which we're in the middle of right now (it's scheduled to end on January 15th in most states).

The green leg--the carrots--mostly consists of the Financial Subsidies, but also includes the Health Insurance Exchanges as well as Price Gouging Protections.

There's two types of subsidies: Premium Tax Credits (which were originally only available to enrollees earning up to 400% FPL), and Cost Sharing Reduction subsidies, or CSR, which can dramatically reduce deductibles, co-pays and so on for families earning up to 250% FPL.

The healthcare marketplaces, or exchanges, are website platforms designed to let people easily compare and shop for private health insurance policies on an unbiased, level playing field.

Most states use the federal exchange, Healthcare.Gov...but 21 states have their own, State-Based Exchanges instead.

The Anti-Price Gouging provision is one of the most successful, but least known parts of the ACA. Insurance carriers have to spend at least 80% - 85% of their premium revenues on actual medical claims in both the Individual AND Group markets. This is called the MEDICAL LOSS RATIO rule.

When you put all of this together you get what was envisioned as the three legged stool. In practice it's MOSTLY worked out, but there have also been some gaps and problems, some of which have been fixed.

There have also been several significant changes in the law. Three of the most significant are:

- First, in 2017, Republicans in Congress zeroed out the individual mandate penalty, effective January 2019.

They technically didn't REPEAL the penalty; they just changed the amount of it to nothing. This led to unsubsidized premiums increasing by around 8%, or roughly $580 per enrollee per year on average nationally. A handful of states have since reinstated the penalty at the state level.

However, since the vast majority of ACA exchange enrollees are subsidized, in practice this means that federal subsidies increased by several billion dollars per year to match the premium increase, which I've labeled the "World's Most Expensive Shim®."

The truth is that regardless of the merits of the individual mandate penalty as a cost saving measure, now that it's been repealed (pardon me...changed to $0), there's virtually no chance of it ever being reinstated in the future at the federal level, even under a Democratic trifecta. It was just too controversial for too long that I can't imagine anyone in Congress will ever want to touch it again.

- Also in 2017, as a result of a long-winding lawsuit brought by House Republicans, the Trump Administration discontinued reimbursement payments for the Cost Sharing Subsidies. Most insurance carriers responded to this by dramatically raising their premiums starting in 2018 in order to capture the revenue they were losing due to CSR reimbursement payments being cut off.

However, some carriers realized that if they raised premiums ONLY on Silver plans, which are the only type eligible for CSR subsidies, this would actually result in premium subsidies increasing to match the rate hikes, which in turn resulted in lower net premiums for many enrollees.

This is known as "Silver Loading," and it's been so successful that Republicans are now trying to reverse themselves on it...and in fact, House Republicans voted to do exactly that last week.

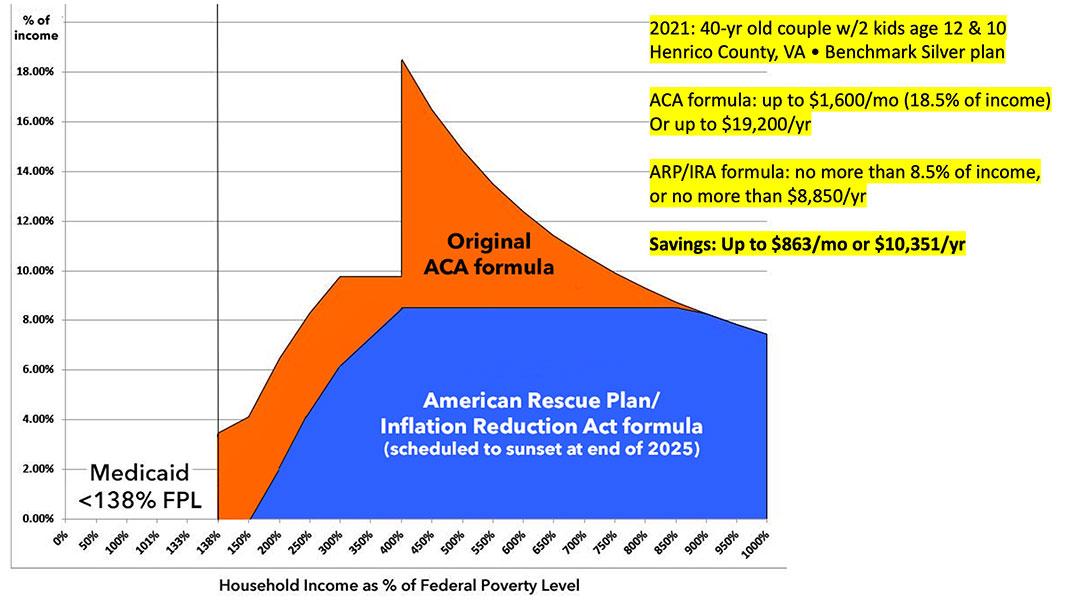

Finally, there was the much-hated "Subsidy Cliff."

While the original subsidy formula was decent for lower-income enrollees, they were increasingly stingy as you moved up the income scale, and they cut off entirely for anyone earning more than 4x the poverty level. This meant that middle-class enrollees were hit from both sides: They earned too little to be able to afford to pay full price but too much to receive financial help.

As I explained yesterday, the only reason the Subsidy Cliff existed in the first place is because keeping the official 10-year Congressional Budget office (CBO) score of the ACA below an artificial threshold was the only way to get enough support for the ACA in Congress at the time.

As I also explained, however, Democrats always intended to eliminate the Cliff and make the subsidies more generous whenever they got another chance to do so...unfortunately, it took another decade for that opportunity to present itself.

So, in 2021, the Democratics in Congress made the premium subsidies significantly more generous, while also expanding them so that NO ONE has to pay more than a maximum of 8.5% of their household income in premiums. The Inflation Reduction Act extended these enhanced subsidies, but only through the end of 2025...which brings us up to today.

The end result of all of this is that enrollment in ACA exchange policies have increased 2.8-fold since 2014, from 8 million people to over 24 million this year. At the same time, ACA Medicaid expansion to all adults who earn less than 138% of the Federal Poverty Level has increased from fewer than 6 million people to nearly 21 million today.

In the end, thanks to the ACA, the uninsured rate in the U.S. has been cut in half from 48 million to 26 million, even as the total population has grown from 312 to 342 million people.

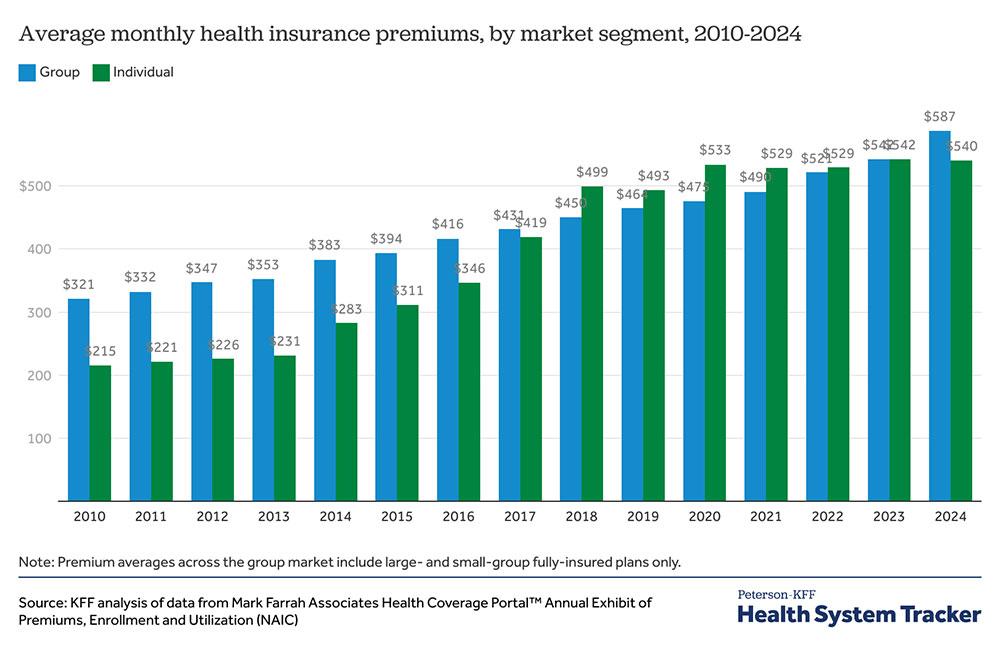

Oh, yeah: One more thing: Take another look at that bar graph from KFF that I posted yesterday which compares average unsubsidized premiums in the individual market against the group (employer-based) market:

Notice how individual market plans pre-ACA cost around 1/3 less than group plans on average? Yeah, that's because employer-based coverage has historically not only been more comprehensive than individual market policies, it also generally covers all of the employees (and their families in most cases) regardless of their medical history.

What's actually happened since ACA regulations were put into place in 2014 is that the regulations for individual market and group market coverage have mostly converged, which is why it shouldn't be surprising that lo & behold, full-price premiums for both are roughly the same on average these days.

The function served by federal tax credits for ACA enrollees is essentially the same as the employer's portion of premium coverage for group policies: That's what makes it affordable for the enrollee, as anyone who's had to suddenly start paying full price for COBRA coverage has learned the hard way.

So remember, when Sen. Lankford wistfully talks about the good old days of premiums averaging just $215/month, remember that the only reason it was that inexpensive was by throwing ~10% of the population under the bus (in some cases literally).

How to support my healthcare wonkery:

1. Donate via ActBlue or PayPal

2. Subscribe via Substack.

3. Subscribe via Patreon.